Conservativism as Postmodernism

The Right is increasingly shaped by the parameters of postmodern culture.

By Matt McManus

For many years there was a refrain that the Left had become a bunch of postmodern relativists and skeptics. Naturally conservatives worried the loudest about how the bogeymen of regular Marxism had been nefariously replaced by the pronounless bogeypeople of postmodern neo-Marxism. But liberals and even a fair share of leftists lamented the slide into what David Harvey called “militant particularism” and identity politics over universalism and rationalism. Plenty agree with Terry Eagleton in The Illusions of Postmodernism that the leftist shift from not reading Lukács and Sartre to not reading Derrida and Spivak was a disaster.

But since the advent of the first Trump administration, it’s been hard to shake the feeling that the conservatives themselves are the new postmodernists. From Trumpists like Rudy Giuliani declaring that “truth isn’t truth” to Jordan Peterson regularly veering perilously close to “it depends on what your definition of ‘is’ is” to Curtis Yarvin calling for everyone to get “Tolkienpilled,” the Right is increasingly shaped by the parameters of postmodern culture.

The Postmodern Condition

Critics of postmodernism have understood postmodernism and postmodernity in several overlapping ways. For them, it usually refers to a series of philosophers and schools of thought, many of which were offensively French. On this reading, postmodern thinkers are keen to deconstruct ancient bedrocks of Western civilization such as truth, justice, Reason magazine and Steven Pinker. An elite phenomenon embracing relativistic identity politics, postmodern philosophy is anxiously presented by critics as permeating the broader culture and distorting it for the worst.

There is a vulgar idealism inherent to these sorts of right-wing critiques, which appeal to intellectuals in no small part because they inflate the significance of their cultural contributions. One of the recurring features of right-wing rhetoric is to veer from locating the sources of social anger in the structures leftists systematically critique to locating social anger in the fact that leftists are systematically critiquing. The idea is that if it weren’t for all these pesky postmodern neo-Marxists endlessly trashing sources of authority, everything would be fine, and everyone would know their place. In more panicked iterations, the excesses of Gayatri Spivak and Judith Butler are nothing less than an existential threat to Western civilization. There is a self-flattering quality to this critique, elevating the importance of those who polemicize against postmodern theory and its influence. The critics of such pernicious nonsense become nothing less than the guardians of truth, reason, and A=A. Metaphysics as chewing gum, as Horkheimer once put it.

Another, richer understanding of postmodernity has been developed by Marxist cultural theory, including the works of David Harvey, Perry Anderson, and, above all, Fredric Jameson. On this reading, postmodern theory is demoted to secondary importance, regarded less as driving than reflecting a broader cultural skepticism and nihilism.

In Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Jameson defines postmodernity as a cultural logic which permeates many spheres: fine art, architecture, theory and philosophy, and, above all, entertainment. While Jameson is sympathetic to the classic view of postmodernism defined by a declining faith in grand or meta-narratives, his own take is that it is better described by a sense that history is foreclosed. Foundational questions about what social form we are going to adopt have been settled in favor of capitalism, leading to a general sense of malaise. Mark Fisher, drawing on Jameson, described this general lack of agency over the society we wish to create as “capitalist realism.” Novel identities and politics can no longer develop. People nostalgically mine the past for a sense of significance.

Jameson draws heavily on the Marxist economist Ernest Mandel, whose classic book Late Capitalism provides a political-economic analysis to ground his account of the emergence of postmodernism as a cultural logic. Mandel famously argued against the center-left view that the welfare state constituted the democratic constraining of unadulterated capitalism. For him, it was rather the fusion of capitalism and the state which enabled capitalism to operate as an ever more encompassing totality. Jameson expands Mandel’s picture to describe how the cultural sphere, which before the twentieth century still retained a kind of artisanal and snobbish independence from capitalism, was increasingly incorporated into the late capitalist totality. Aesthetics and intellectual work, previously the purview of well-heeled, snobbish aristocrats and bourgeois social climbers, is increasingly commodified and replicated on a mass scale.

This means art, culture, and theory increasingly lose any independent capacity to challenge the status quo. At best, postmodern politics can borrow a sense of significance only through nostalgic symbology or pastiche, assembling and reassembling the various resonant symbols and identities of the museum-like past to scrupulously avoid the impossibility of creating the new. In postmodernity there can be no art that offers a challenge beyond the most superficial efforts to shock and ironize the sacred, since the effect is to suggest nothing can change.

The Rise of Postmodern Conservatism

Jameson’s analysis can help us understand why postmodern conservatism emerged and quickly gained such enormous appeal in the twenty-first century. Archaeologies of the Future has a melancholy quality. Jameson notes how even in speculative fiction, it is very rare to find anyone who thinks that we are going to improve upon capitalism—even where, like Philip K. Dick, they acknowledge its nihilism. Today tech billionaires like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk muse openly about transhuman futures, the colonization of new worlds, and the formation of AI superintelligences. All this is easier for them to imagine than a world where oligarchs aren’t at the summit. Somehow eternal life for the rich may be possible, but free buses or public grocery stores are fantastically utopian.

In these conditions of capitalist realism, debates about economic questions and redistribution inevitably become sidelined to contests around identity and values. This is compounded by neoliberal capitalism’s dissolution of traditional “sources of the self,” as political theorist Charles Taylor put it in his book of the same title. Marx and Engels predicted that “all that was solid would melt into air” as the most revolutionary mode of production in history expanded its power of creative destruction across the globe and all spheres of life. The postmodern condition is consequently one where the intensity of debates about identity is proportional to the feeling that the sources of our self are slipping away.

It shouldn’t surprise us that reactionaries have been the main beneficiaries of these intense feelings. As Terry Eagleton noted in The Illusions of Postmodernism, conservative philosophers from Burke through Gadamer have been very comfortable with the idea that politics should focus on respect for traditional identities and forms of knowledge while denying the “rationalist” impulse to exercise freedom and intelligence to remake the world for the better. Moreover the emphasis on the historical contingency of knowledge and rejection of universalism and rationalism characteristic of the postmodern epoch gels well with the instincts of many reactionaries. Joseph de Maistre famously insisted that rationalistic philosophy was a destructive force for corroding the dogmas and traditional authorities into which one was born, and rejected the very idea one could talk about human beings in general rather than Frenchmen, Englishmen, etc.

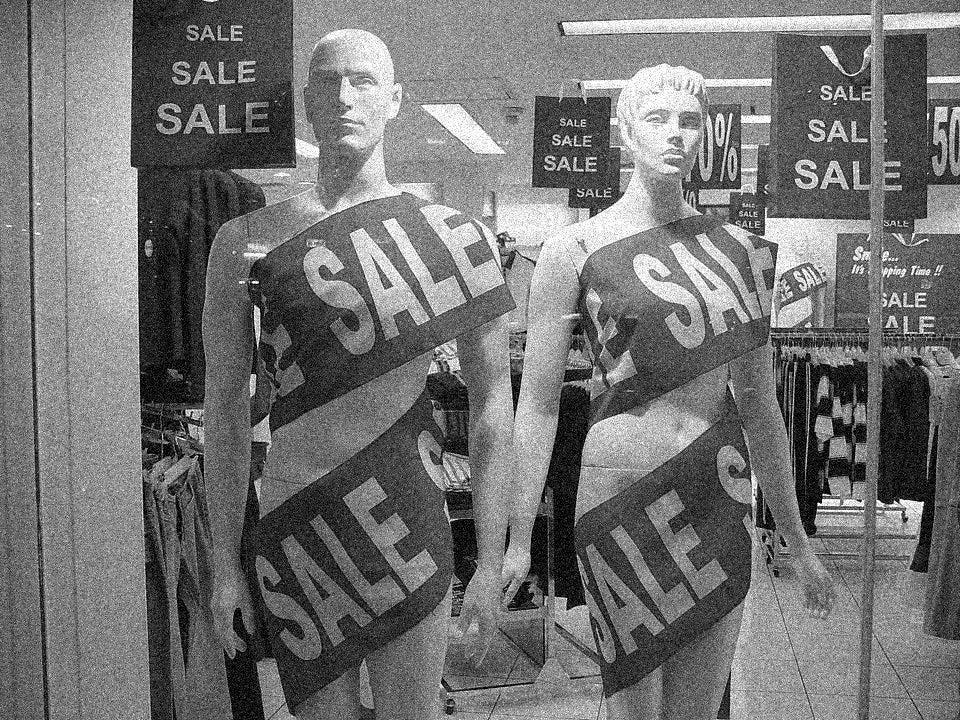

Under the conditions of postmodernity, these conservative instincts can mutate into a distinctly postmodern conservatism. Lacking traditional sources of selfhood grounded in longstanding material and historical practices, postmodern conservatives turn to hypercurrent media technologies to reify a distinctly pastiche-like sense of identity as a locus of meaning. They draw selectively from the cultural signifiers of the past: whether Catholic nationalism, Reaganite cosplaying, the abiding nostalgia for the good ol’ days of independence and empire, and so on. These reified identities are fragile because they are so often a transparent construction, owing little to the material realities and practices postmodern conservatives experience.

Postmodern conservatives are paradoxical in both normalizing and naturalizing the traditional identities they construct while simultaneously agonizing about corrosive cultural forces and actors that endlessly threaten them. Rather than pin the blame on capitalism, the blame for the disintegration of the self is projected onto the unworthy and dangerous alongside their elite liberal and progressive allies. Migrants, radical professors, critical theorists, gay activists, and Ibram X. Kendi must all be opposed and eliminated to create a safe cultural space for postmodern conservatives and those they consider worthy.

This fixation on identity aligns with the strategic forms of epistemic skepticism postmodern conservatives adopt. They are adept at expressing incredulity towards meta-narratives and appeals to rationalistic authorities, but this doesn’t make the majority of them comprehensive relativists and nihilists. Instead, like figures on the Right going back to Edmund Burke, they appeal to skepticism towards reason precisely to enable unskeptical deference to authoritative figures and traditions that align with their identity and value system. This is facilitated by the postmodern collapse of faith in rationalistic authorities and argumentative reason. What replaces it is a kind of Schmittian decisionism based on friend and enemy identities, with one’s ideology as protected from needing to make an account of itself.

This is all aided by an increasingly comprehensive right-wing media sphere, which insulates postmodern conservatives from alternative perspectives and reinforces preferred narratives. More importantly, as Baudrillard would note, the hyperreality of postmodern media has proven an extraordinarily fruitful arena for adept right-wing influencers. With digital media increasingly disconnected from representing the material world, the appeals to affect, agonism, and undialectical bifurcation into “good and evil” which the Right have always been deft at manipulating have been able to flourish.

Some of the major influencers and figureheads in the postmodern media-sphere are cognizant of this opening for the pitch. Many are unapologetic about prioritizing framing and feeling over deference to the truth. The late Charlie Kirk embodied this form of post-modern conservatism in his book Right Wing Revolutionaries:

Americans are phenomenal salesmen, and we love a good sales pitch. Sometimes, we love the pitch more than the product. Only about one in seven Americans has Geico car insurance, but most of us can remember half a dozen Geico ads…. Americans are, in short, the most successful people in the world at marketing and advertising. In other words, Americans are experts at a type of friendly-looking deception because the heart of advertising is framing. In advertising, framing is about shaping a person’s perception of their own needs. “You have a problem, and this product will fix it.” “You should associate this drink with having a fun time.”…. You can guess where I’m going with this. The political battle in America isn’t just a battle over policy. It’s an advertising battle. And that means it’s a battle between two sides over whose framing is better.

On Kirk’s telling, even “friendly deception” was permissible if one is engaging in political framing, which ultimately is just marketing and advertising writ large. Kirk urged conservatives to “police your own thinking” to prevent even imagining the world the way progressives might suggest. While conservatives might “not be fully certain what is right in a given context, we can definitely be certain the left is wrong.” Kirk concluded by suggesting conservatives chase a “Luke Skywalker vs Darth Vader attitude toward every issue possible.”

Conservative influencer Chris Rufo echoes this point in more posh language. In an interview, Rufo declared that the “man who can discover, shape and distribute information has an enormous amount of power. The currency in our postmodern knowledge regime is language, fact, image and emotion. Learning how to wield these is the whole game.”

Postmodernism has often been accused of generalizing a kind of radical skepticism. If so, it is an emphatically un-Socratic skepticism, one which weaponizes uncertainty to banish critical thinking in the name of affirming one’s preferred dogmas. This quality is on full display in Rufo’s America’s Cultural Revolution, where Rufo manages to reject a huge array of left-wing thinkers without ever feeling compelled to argue against their claims. The goal of discourse is no longer to question one’s priors, but to affirm the opinions one already feels to be true. By chasing affirmation rather than critical reflection, the postmodern conservative entrenches a culture of performative banality whose sole goal is to relieve ordinary people the burden of thinking for themselves through the industrial production of thought-terminating clichés.

The Future Remains Cancelled

Without a doubt, much of what has been written here could be applied to the political Left as well. The fixation on identity, the nostalgic reverence for militant communist movements past, and the intense agonism which relishes manufactured conflict are all very much present. But the Left is fundamentally committed to equality, which has an inherently universalistic dimension to it. Indeed, one of the reasons the Left was so successful in the heyday of rationalist optimism was precisely the conviction that reason could be applied to successfully build a better world for all. This conviction can be found in everyone from liberal socialists like J.S Mill to Friedrich Engels’s insistence that in the future communist society, divisive politics will be replaced by the rational administration of things for the common good.

In a postmodern era, this aspirational rational universalism has been a very hard sell. By contrast, the fundamental cynicism of postmodernity has proven fertile manure for postmodern conservatism to flourish, appealing to deep instincts of superiority that license putting one’s self and the “America” you identify with first. After all, if a world where the free development of each and all will always be a pipedream, you might as well indulge in mankind’s oldest quest: searching for a superior moral justification for selfishness.

In Rufo at al’s ethno-chauvinism and nationalism, we find the culmination of Jameson’s anxieties about how capitalism has completely colonized the cultural sphere and neutered even the prospect of critical thinking about transformative alternatives. The truth or falsity of political identities and positions as a measure of any accurate reflection of reality was irrelevant; they’re only to be appealed to as empty affirmations. We stand for TRUTHBOMBS! and Western CivilizationTM. What really matters is the battle over “framing” and “marketing” through which one defines who people are and what they should believe in. To succeed one must consciously banish complicating facts and alternative ways of thinking about things, strategically applying skepticism to all rival viewpoints while uncritically and dogmatically propagating one’s own with protective love. The postmodern sophist looks warily at everyone else’s convictions while sentimentally tending their own. It is an insular and radically deflating way to perceive the world which demands, to paraphrase Benedict Anderson, big feelings for very small ideas.

Unfortunately this radical smallness and vulgarity has not neutralized the appeal of postmodern conservatism. Indeed it has facilitated it. In a postmodern condition, where there is no alternative to capitalism, millions have turned to memed nostalgia as a source of agonistic meaning. It provides a sense of identity and sometimes even the simulacrum of youthful, anti-system populism, even where the actual goal of postmodern politicians like Trump is to cut funding for the poor and middle classes to redistribute hundreds of billions to his fellow sclerotic oligarchs. Until the Left is able to offer a genuinely realistic alternative vision that catches hold and directs the imagination towards something better, the socialist future will remain indefinitely cancelled.

Matt McManus is an Assistant Professor at Spelman College and the author of The Rise of Post-modern Conservatism and The Political Theory of Liberal Socialism amongst other books.